Midwest Region

Regional Offices

Peoples Company - Bloomington

Midwest

Peoples Company - Cascade

Midwest

Peoples Company - Champaign

Midwest

Peoples Company - Cumming

Midwest

Peoples Company - DeWitt

Midwest

Peoples Company - Fremont

Midwest

Peoples Company - Independence

Midwest

Peoples Company - Indianola

Midwest

Peoples Company - Kasson

Midwest

Peoples Company - Kearney

Midwest

Peoples Company - Lincoln

Midwest

Peoples Company - Norfolk

Midwest

Peoples Company - Omaha

Midwest

Peoples Company - Oswego

Midwest

Peoples Company - Plainfield

Midwest

Peoples Company - Wapakoneta

Midwest

Peoples Company - Wayne

Midwest

Regional Listings

Warren County, IA

12183 Nevada Street

Indianola, IA 50125

Scenic 16.12-Acre Wooded Acreage with Pond, Building Sites & Hunting Just South of Indianola, IowaPeoples Company is pleased to present this 16.12-acre wooded property ideally located just south of In...

ACRES M/L

LISTING

Wayne County, IA

1066 S56 Highway

Russell, IA 50238

Luxury Country Retreat with Premier Outdoor Experiences - Escape to the beauty of Southern Iowa with this stunning 85.63-surveyed-acre m/l lifestyle and recreational retreat in northeast Wayne County....

ACRES M/L

LISTING

Warren County, IA

8145 Pierce Street & County Highway R57

Indianola, IA 50125

Warren County, Iowa Land For Sale – Discover a fantastic opportunity to own 23.65 acres m/l of premier recreational and residential land in scenic Warren County, Iowa. This beautiful tract features ...

ACRES M/L

LISTING

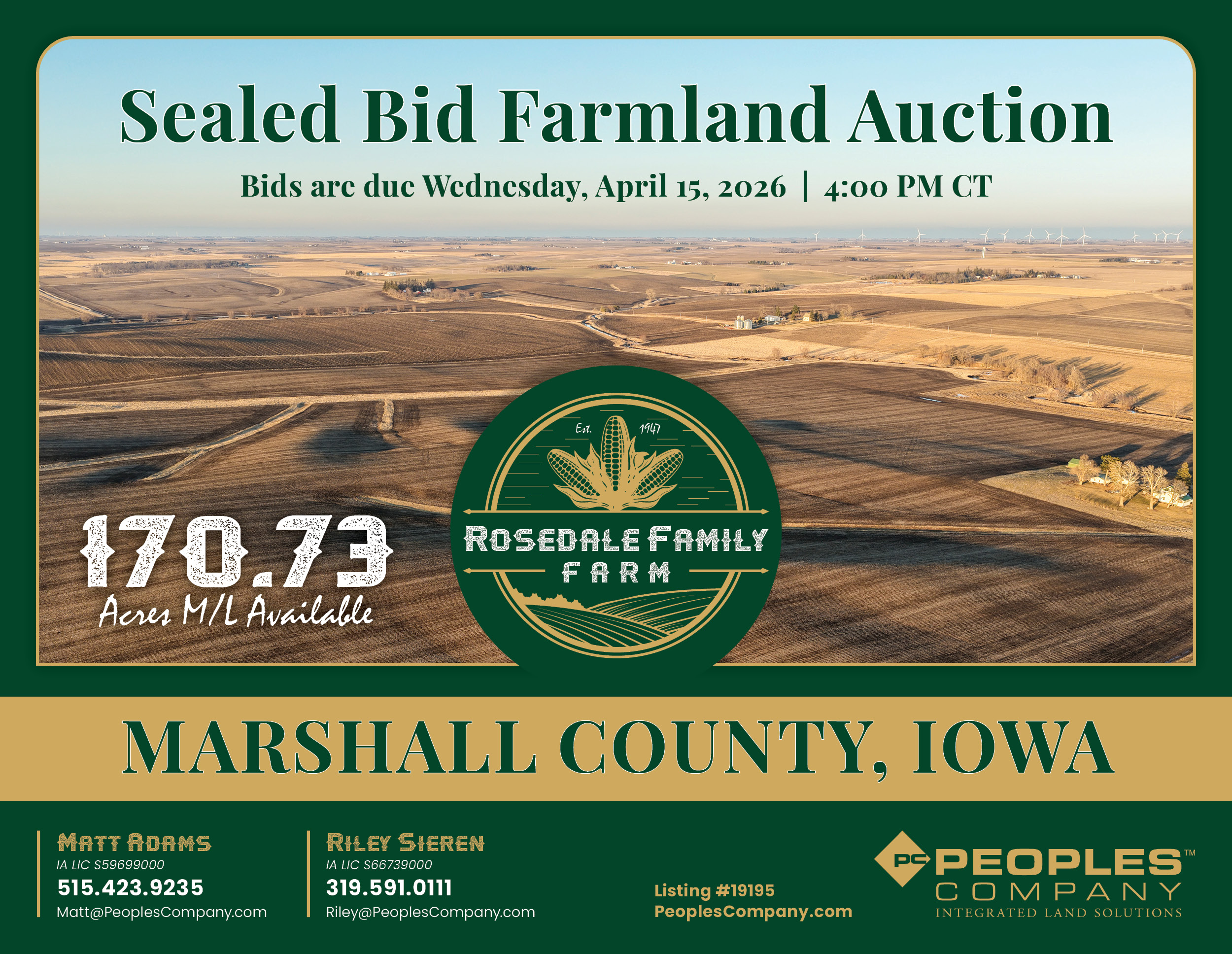

Marshall County, IA

IA Highway 330

Albion, IA 50005

Marshall County, Iowa Sealed Bid Land Auction – Peoples Company is pleased to represent 170.73 acres m/l of premium Marshall County, Iowa farmland, ideally located just off Iowa Highway 330 and with...

ACRES M/L

AUCTION DATE

LISTING

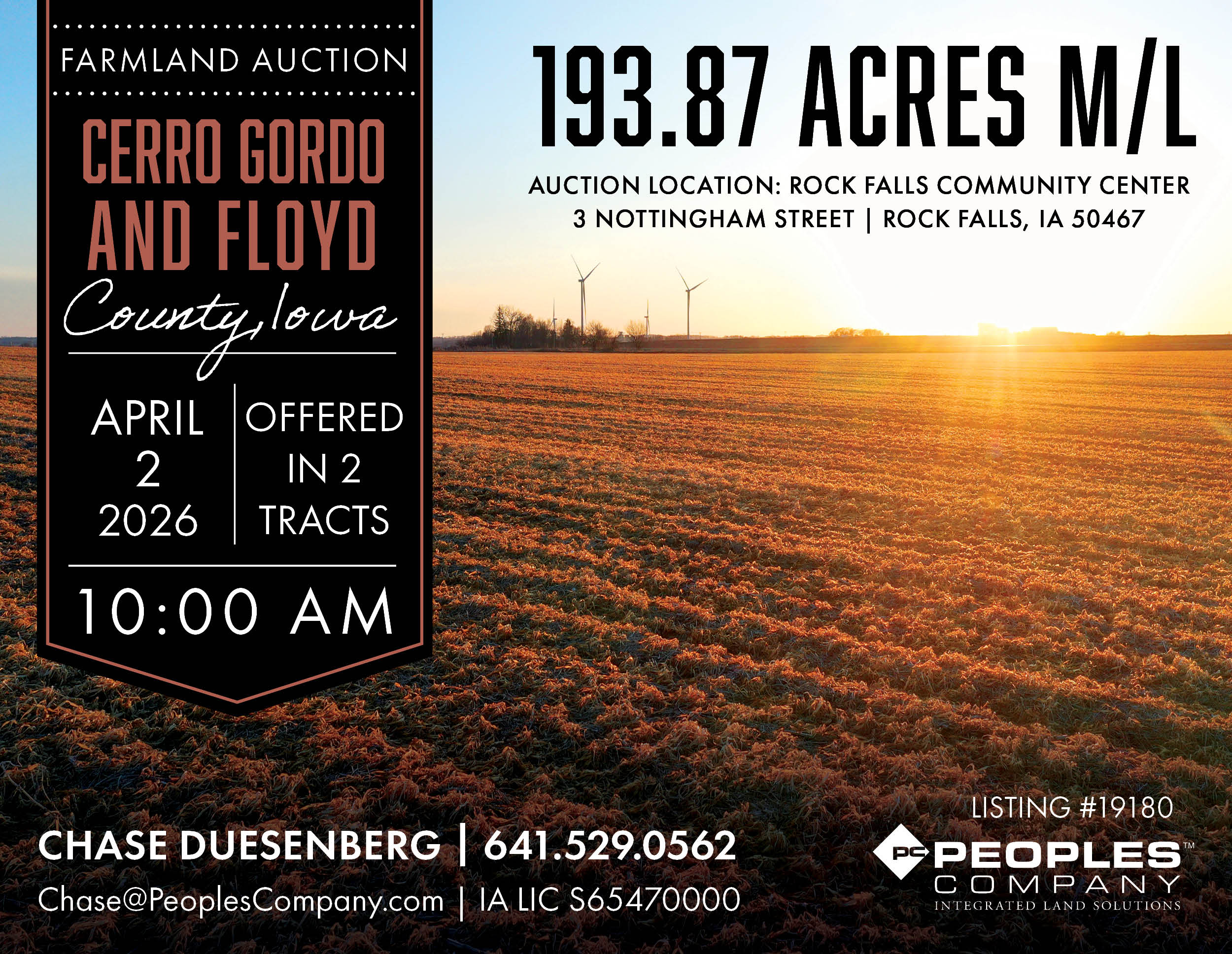

Multi-County, IA

Cerro Gordo & Floyd County

Mason City & Rockford, IA 50468

Cerro Gordo & Floyd County, Iowa Farmland Auction - Mark your calendars for Thursday, April 2nd, 2026! Peoples Company is honored to represent the sale of 193.87 acres m/l, with Tract 1 being located ...

ACRES M/L

AUCTION DATE

LISTING

Cumming, IA

1619 Sunset Harvest Aveue

Cumming, IA 50061

Welcome to the Homestead Townhomes in Middlebrook Agrihood, one of the Des Moines metro's most unique communities. This END UNIT thoughtfully designed two-story townhome offers an open main level feat...

ACRES M/L

LISTING

Wayne County, NE

566th Avenue

Winside, NE 68790

Peoples Company is pleased to present 320 acres of high-quality farmland located near Winside in Wayne County, Nebraska. The property includes 307.5 FSA cropland acres with primary soil types consisti...

ACRES M/L

$12,031 / ACRE

LISTING

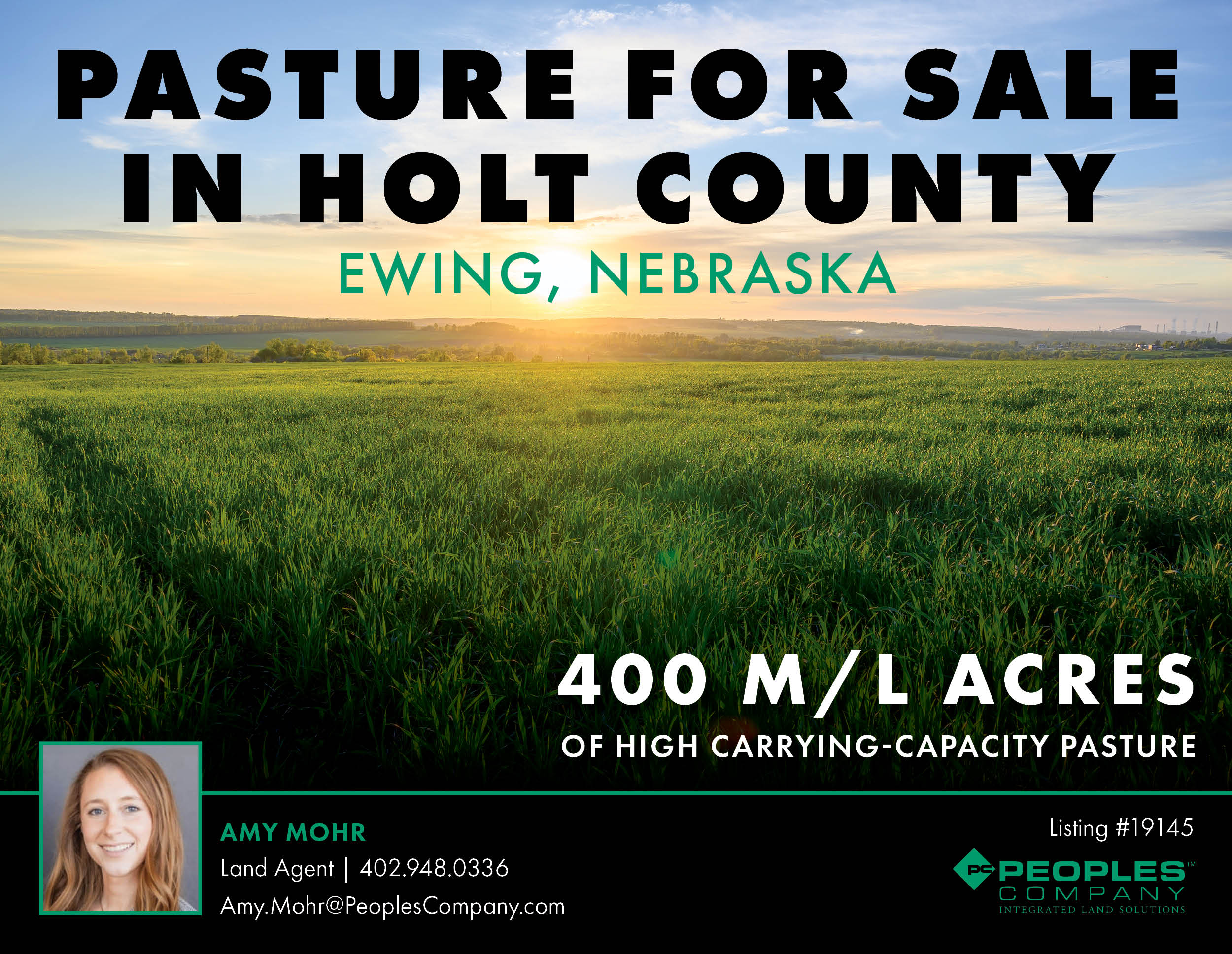

Holt County, NE

502nd Avenue

Ewing, NE 68735

Peoples Company is pleased to present 400 m/l acres of high carrying-capacity pasture in east-central Holt County, Nebraska, located just northwest of Ewing. This property allows for strategic grazing...

ACRES M/L

$3,750 / ACRE

LISTING

Davis County, IA

Silver Trail

Floris, IA 52560

While many recreational farms come to market each year, very few offer this level of completeness or possess the qualities needed to consistently create a high-quality outdoor experience. This turn-ke...

ACRES M/L

LISTING

Davis County, IA

SIlver Trail

Floris, IA 52560

This 191.36-acre m/l hunting and recreational farm in Davis County, Iowa, near Floris offers a rare blend of high-quality timber, established food sources, income-producing acres, and functional impro...

ACRES M/L

LISTING